By David Ott

By David OttThe “Little Book” series launched with a short book about a magic formula that promised an easy way to find would beat the market. Normally, this premise would be enough for me to pass right by, but it was authored by a highly respected hedge fund manager who had racked up more than a decade of annualized performance of around thirty percent (before incentive allocation, of course).

The sixth installment in the series is The Little Book That Builds Wealth, by Pat Dorsey, the director of stock analysis at Morningstar, Inc. Although the title is shockingly disconnected with the contents of the book, it is an insightful review of competitive strategy with a remarkable number of real world examples that support his analysis.

This book is not about building wealth (the word wealth is used a scarce three times throughout), but about identifying whether or not a company has an ‘economic moat.’ An economic moat is the homespun name that Warren Buffet uses to describe whether or not a company has a sustainable competitive advantage.

As Morningstar and Dorsey see it, there are essentially four sources of competitive advantage (or an economic moat in their parlance):

- Intangible Assets such as brand names and patents.

- High Switching Costs like the cost of purchasing new equipment or software.

- Network Economics, which refers to a ‘closed loop’ business that builds on itself. For example, telephones aren’t very useful without other people who use telephones.

- Cost Advantages that can come from scale, processes, legacy or geography.

Each one of these moats is described in terrific detail with plenty of examples. While Coca-Cola is an obvious example of a successful business built on a strong brand name and everyone knows that Wal-Mart typifies cost advantages through their vast scale, Dorsey provides multiple real world examples for each kind of competitive advantage and how it translates into business success.

Generally these are all considered barriers to entry under Porter’s five forces analysis. Morningstar generally neglects other some of Porter’s forces like the intensity of competitive rivalry, the bargaining power of customers and the bargaining power of suppliers. Instead, they choose to focus on the threat of new competitors and the threat of substitute products and services. This seems like a reasonable choice on their part, since they don’t want to simply repeat Porter’s work and they can make the argument that some of these unmentioned forces fall under their more broad definitions.

While the descriptions and examples are all very good, the book stops short of being great since it really only describes what to look for in a business. It doesn’t offer much in the way of figuring out whether or not a good company will make a good investment. For example, we can use this book to determine that McDonalds is a great ‘wide moat’ company, but obviously, it makes a huge difference what price we pay to become a part owner in this enterprise.

Dorsey makes this point at the outset of chapter twelve and dedicates a only 27 out of 200 pages to outlining the basics of valuation. Valuation is one of the most important and difficult aspects of investing, so it’s a disappointment that there is such scant coverage of the topic in the book. It’s a shame since Morningstar has a detailed valuation methodology that they have created for their stock star ranking system that could have filled another book of the same length, leading me to argue that they only told half of their story. I suggest that this book be re-titled to “The Little Book of Identifying Economic Moats.”

One of the nice things about reviewing a book like this is that there is real performance based on the strategy. Cranking out investment platitudes is easy, but backing it up with actual results is far more useful and interesting.

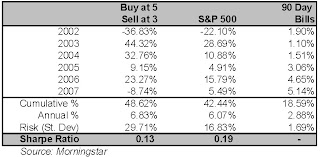

The table shows the performance of buying stocks with a five star rating (usually a wide moat company trading with a substantial margin of safety) and then sold when th e stock becomes a three star holding (the moat may still be intact, but the stock is trading at or around ‘fair value.’ Morningstar presented their results using three methods for buying and selling and the table reflects the data with the best results. Additionally, the table only reflects full year data.

e stock becomes a three star holding (the moat may still be intact, but the stock is trading at or around ‘fair value.’ Morningstar presented their results using three methods for buying and selling and the table reflects the data with the best results. Additionally, the table only reflects full year data.

Although Morningstar deserves high praise for beating the S&P 500 for the six complete years available, it wasn’t a free lunch and it would be hard to argue that this strategy alone builds wealth. Although the Morningstar returns are about 15 percent higher than the S&P 500, the volatility, or risk, was about 75 percent higher. This disparity is reflected in the Sharpe Ratio, which shows that the S&P 500 had better results on a risk adjusted basis.

It is also important to note that we can’t see the details of how these results were generated. We can’t tell if it was an overweight in energy stocks which have been extremely good over the past five years, or if they had substantial investments in mid and small cap stocks, in which case the S&P 500 may not be the best benchmark. We also can’t see other characteristics like turnover, which appears high based on the fact that I receive an email nearly every day with between two and eight new five star stocks. On an after tax basis, these results are likely to be far worse than the S&P 500.

So, we know that Morningstar hasn’t found the magic bullet for investing – no surprise there. With that said, the book is worthwhile as it helps develop a framework for identifying good businesses, which is a critical component of successful investing. I commend Morningstar for putting together a solid process and laying out the results for the world to see and wish that more firms were willing to do this with such thoroughness and integrity.

June 10, 2008

____________________________________________

Recommendation: Market Perform

The Little Book That Builds Wealth:

The Knockout Formula for Finding Great Investments

By: Pat Dorsey, CFA

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey 2008

ISBN: 978-0-470-22651

No comments:

Post a Comment